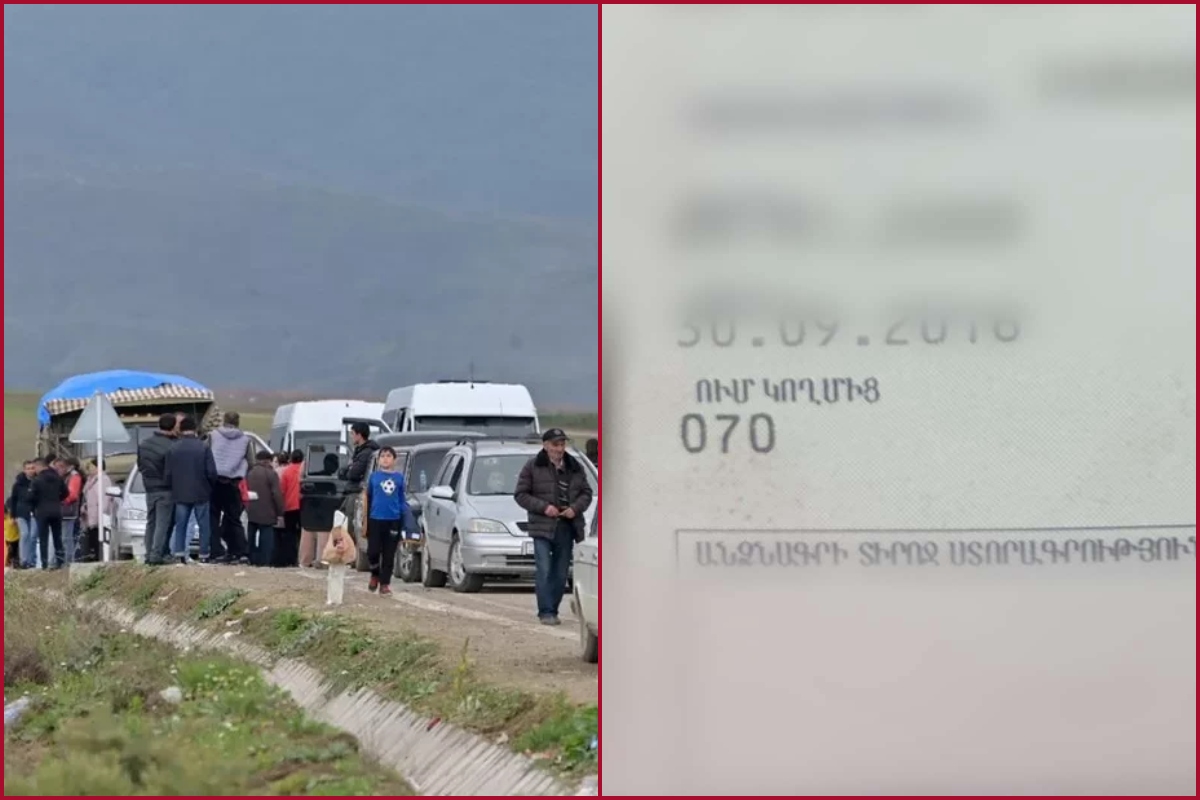

Since September 19, 2023, approximately 115,000 people have relocated from Nagorno-Karabakh to the Republic of Armenia. This information was provided by the Ministry of Internal Affairs in response to an inquiry from Iravaban.net.

It should be noted that prior to this period, after the 2020 displacement, some Artsakh residents had already established residence in Armenia.

As of February 20, 2025, 116,157 individuals hold refugee status, of whom 6,937 have been granted citizenship of the Republic of Armenia.

Marianna Avagyan, a lawyer with the NGO Network for Protection of Rights of Artsakh Armenians, notes that this is an extremely low figure, especially considering that those who received temporary protection (refugee) certificates are eligible for a simplified citizenship procedure.

“One and a half years have passed since the forced displacement after September 19, 2023, and such a small number of people accepting citizenship clearly indicates that the majority of Artsakh Armenians do not want or are not rushing to acquire Armenian citizenship. This is due to several significant factors that have legal-political, psychological, and historical-cultural roots.

The first and perhaps most important reason is that Artsakh Armenians fear that after obtaining Armenian citizenship, the Artsakh chapter will close in the international legal and political field. They believe that in that case, they will no longer have the opportunity to return to Artsakh—their birthplace, homeland, their homes. From an international law perspective, Artsakh Armenians have legitimate concerns that by obtaining Armenian citizenship, they may lose their rights as displaced persons, which includes the right to return,” she said.

According to the lawyer, another reason for not accepting citizenship is the deep distrust towards the current government of the Republic of Armenia. She emphasizes that this distrust is conditioned by the policies pursued by the state, positions publicly expressed by high-ranking officials, and intentions to make continuous concessions.

“As a result of numerous meetings and interviews with Artsakh Armenians, it became clear that those who have received Armenian citizenship or those who intend to obtain citizenship mainly indicate that they make this decision not voluntarily, but out of necessity. They mentioned that when applying for jobs, employers mandatory require Armenian citizenship. Armenian citizenship is also required to access a number of social benefits and support programs. A particularly important incentive is the opportunity to benefit from the housing provision program, for which Armenian citizenship is a mandatory prerequisite.

Thus, the decision of Artsakh Armenians to acquire citizenship is mainly determined not by subjective preference, but purely out of vital necessity—based on the practical need to access basic socio-economic rights in Armenia,” said Marianna Avagyan.

Hasmik Sargsyan