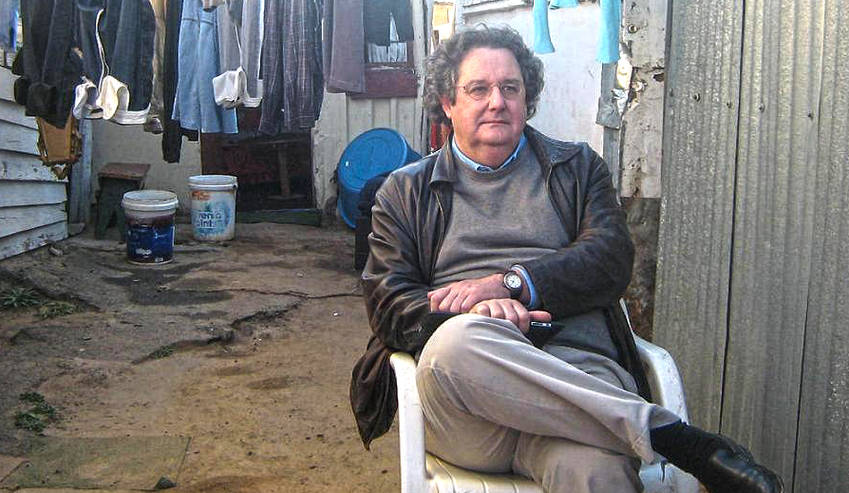

Experienced in both dictatorial and democratic ways of doing journalism, Anton Harber has never stopped fighting for freedom of speech and transparency. Throughout his career, he founded many newspapers such as The Spring Advertiser, The Sowetan and, above all, the Weekly-Mail, now known as Mail&Guardian.

After the fall of the apartheid regime Anton Harber worked for the future of journalism in South Africa, training and raising many journalists. Today, twenty-seven years later, he proudly contemplates the golden age of journalism in South Africa.

In this interview to Iravaban.net, he also reviews the situation of journalism in the past and talks about the future challenges for the profession.

– How is it like to be an investigative journalist in South Africa nowadays?

Nowadays, we have a fantastical level of freedom. Investigative journalists are able to do a lot now. In fact, the last two years have also been a bit of a golden age for investigative journalism. Let me give you the full picture.

We are having a very big corruption story here about a particular family called “Gupta”, who had a very close relationship with the president and his family. That story has been exposed by two or three groups of independent investigative journalists who have done incredible work during the past year or two. Because of that case of corruption, the president is expected to resign in the next day or two. The huge part of what has led to that is the work of a small number of investigative journalists.

– What were your first steps in journalism? How did you create the Weekly Mail?

Since I was young, I’ve wanted to become a journalist. When I finished my degree at the university in 1980, I struggled to get a job in journalism. Thus, I had to go to work for a small town newspaper covering the small local stories. Then I moved to a newspaper called The Post, which was a Black newspaper. It was becoming increasingly important in politics in that period. It was really a Black newspaper and I am not Black. All the reporters were Black. It was a great place to learn a lot about what was going on in this country. Then I was fortunate to get a job in the Daily Mail, the leading newspaper of that time, as a political reporter. The newspaper was closed for political reasons in 1985 and that is how we started the Weekly Mail; if the government closed a newspaper, people started another one. If they arrested journalists, then others would step in, they would go to courts and fight the restrictions and laws. We were pushing back all through the years. But I was privileged because it was much harder for Black journalists. At least I had some protection.

Source: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2011-07-14-anton-harbers-diepsloot-a-slayer-of-township-stereotypes/#.WsNnOC5uaUn

– As a co-editor of The Weekly Mail, now the Mail&Guardian, you were prosecuted by the apartheid government in 1988. How was the situation back then?

During the Apartheid there were many restrictions for the media. There were lot of laws restricting what you could do, and particularly in the last years of the Apartheid we lived under a state of emergency. There were always powers to arrest candidates, detain journalists, confiscate newspapers and prosecute us for breaking the emergency regulations.

Mail&Guardian used to operate in the great area of law, trying to do as much as we could and pressuring the boundaries of law. But we were an anti-apartheid newspaper. Thus, our newspaper was confiscated quite often, sometimes our journalists were arrested and I was certainly prosecuted many times myself. When Nelson Mandela came out of prison, I had about ten cases going on where they were prosecuting me for breaking the state emergency regulations.

– How were you feeling about the situation, did you fear for your family?

I had to be aware that I could be arrested at any time. They also closed the newspaper. So it was a very high risk and sometimes there was even extra-legal activity. For example, once my colleague’s house was set on fire, and once they fired bullet shots at my friend’s door. It was quite a terrifying time to operate and very-very risky. But in a sense, we saw those were the dying days of the apartheid so we knew we had to carry on until the system collapsed. One day I got a message saying that Mandela was coming out of prison and that we could do what we liked.

– How were those first years of democracy?

It was certainly very free. The first years were extraordinary because there was no rule, we could do whatever we liked. But we really had to re-learn our journalism. We had learned a certain kind of journalism to operate under censorship. Actually, when the country becomes a democracy, you have to learn a new set of rules and a new way of doing journalism, in fact a more traditional one. When there is a new attitude towards the law, I suppose one thing you have to do is to learn how to respect it and work within the law as we do it now in democracy.

– Regarding your experience in training journalists, which were the main instructions given and what abilities were you inculcating in them?

We had to train young journalists, because under the apartheid it was very difficult for a Black person to become a journalist. Thus, with the support of funders we brought here young Black people who wanted to be journalists and trained them to be ones. Most of all we were looking for people who had independent mind. We really felt that under apartheid and afterwards, that was the most important thing to find, that is: people who can think and act independently.

However, a lot of young Black people had a problem. They had special relations with the ANC (African National Congress) during the days of apartheid. But we really had the courage to teach them to act as independent journalists and to enable them to write about and criticize the ANC, once it became the government.

– How did the relations with the ANC change after that?

That was very difficult because of the good relations with the ANC in the past. When it became the government and we started to criticize them, they really gave us quite hard times; they told our people “We thought we were friends”. Our answer to that was that maybe we were their friends but we were also journalists, and if we wanted to produce useful and truthful journalism, then we had to be independent.In fact, that independence has been crucial in the last few years in terms of exposing corruption in the government.

– What is the cooperation between lawyers and journalistslike in South Africa?

Under apartheid, the right thing we did in the newspapers we operated, the so-called “alternative newspapers”, was to use lawyers in a different way: Instead of using lawyers as most of the media did, telling us what we cannot do because it is illegal, we said to the lawyers “we are not interested in that, we are interested in you helping us find ways to do it. We are interested in you telling us how to get this information, without entering into trouble”. And that definitely gave us a different attitude towards lawyers. And we found out that if you work with lawyers all the way through your story you can work hard being safe.

– Do you have examples of cooperation between them?

Now we run a project at the university called the “Wist Justice Project” and this project is put together by a human rights journalist and lawyers. They work together to expose problems in our justice system, using both the media and the court to address these problems. We find that if journalists work closely with lawyers they not only just write a story, but they often prepare a case to take it to the court; the journalists use their investigative abilities and the lawyers use their legal skills and they fit excellent together.

– Is there a mechanism of getting information from the government in which journalists and lawyers work together?

We have something called Promotion of Access to Information Act. That act gives one the right of access to any information held by the State. However, it hasn’t been successful or effective because there is no penalty in case the government doesn’t want to give you the information.

– Finally, what are the current challenges for investigative journalism in South Africa?

One big challenge is that our State Security Agency (SSA) does put pressure on our lawyers and journalists, andoften illegally. The SSA people aresometimes following and harassing journalists. The government has been trying to put a new Secrecy Law in place. That would make it much more difficult to publish investigative journalism pieces. However, they haven’t been able to put it in place because there had been a great deal of resistance from civil society. The Law was passed two years ago by the parliament but it hasn’t been promulgated.

Interview by José Nicolas Dominguez Mendoza,

EVS Volunteer at the Armenian Lawyers’ Association

Author of the Idea: Astghik Karapetyan